“Be weird,” was one piece of advice that Ingrid Rojas Contreras offered during an author talk at The Sanctuary (a virtual writing community for women of color). Or so I thought. Looking back at my notes, she might have said, “be strange.” Strange and weird are odd bedfellows. I’m embracing both.

On mornings when I take a walk, I sometimes stop next to a creek. At first, it was to sit on a nearby bench, but the water wasn’t actually visible so now I go down closer to the bank. I take a few breaths, not necessarily deep, just whatever my body happens to be needing at that moment. Most times, I bend my knees a little, raise my hands up with each inhalation, lower them with each exhalation. I thought this was a chi gong or tai chi movement, but I looked on-line and can’t find this exact exercise. But I’m trying to not let that bother me.

I used to take yoga classes regularly. In one lesson, the instructor told us to bend into a standing forward fold and then she said (at least I’m pretty sure she said) to “play around”. She then suggested (at least I’m pretty sure she suggested) that we experiment with stance, foot placement, arm placement, head and hip movements. So I started doing what I thought were her instructions, moving my feet different distances apart, bending at and grasping elbows. Most of the yoga classes I’d been to at that point had been pretty precise about where to place body parts and so I was a little surprised. Still, I took it to heart and thought, “this is actually really nice to just kind of see how all of these different positions feel in my body.” It was somewhat freeing to not feel as though I had to do exactly what the instructor told me to do. I don’t remember exactly what position I was in when she came over and stood next to me and said that what I was doing wasn’t actually a yoga posture.

Come again? I thought.

Now you might understand why now, looking back, I sure/ not sure that the instructions were to play around and experiment. That’s one of the things gaslighting does to you: makes you unsure that you heard what you heard. A yoga studio is an unexpected place for gaslighting. In retrospect, a lot of unexpected things are always going on in the yoga studios I’ve gone to. Or maybe it’s exactly how these “systems” are supposed to work. I came out of yoga with a lot of unfortunate ideas about how to treat my body, a lot of thoughts around how I’m “supposed” to hold my body and move my body and use my body. It’s unfortunate how a practice that was developed in the east to be liberating has ended up so confining in the west.

I haven’t gone back to yoga for a few years now, but I have appreciated the work of Susanna Barkataki to decolonize yoga.

Standing on the edge of the creek, breathing and moving in ways that just feel “right” to me (not because an instructor is telling me) is me being strange. Or weird. This whole practice of mine takes all of about a minute. And for the first few seconds of that, all I can think about it, “what if someone sees me?” Eventually, maybe by the third or fourth breath, the trees and the water give me courage to shake that thought off. They do see me. And what I’m doing (breathing and moving) doesn’t bother them one bit.

Being weird is something I have to be intentional about.

I just listened to an episode of Lori L Tharps’s podcast My American Melting Pot called “Talking to Our Kids About Race”. There’s loads of information in that episode, but one part of it relates back to this idea of being strange. Or weird. Or odd. One of the guests talking about how you have to be intentional about education yourself about race and exposing yourself (and your children) to racially diverse experiences. She used the example of how the algorithm on Netflix works. If you’re always watching British period dramas, Netflix is going to think that’s all you watch and will only recommend more British period dramas to you. And they will be mostly white.

I few years ago before I quit Twitter, some of the targeted ads I was seeing were for Black hair salons. I’m not Black but I was evidently engaging in such a way that the algorithm seemed to think I might be. In no way shape or form was having Black hair salons on my feed damaging to me. In fact, alongside these advertisements, I was also exposed to increasingly varied and diverse content, much of which spoke to me even though I’m (with apologies) not Black.

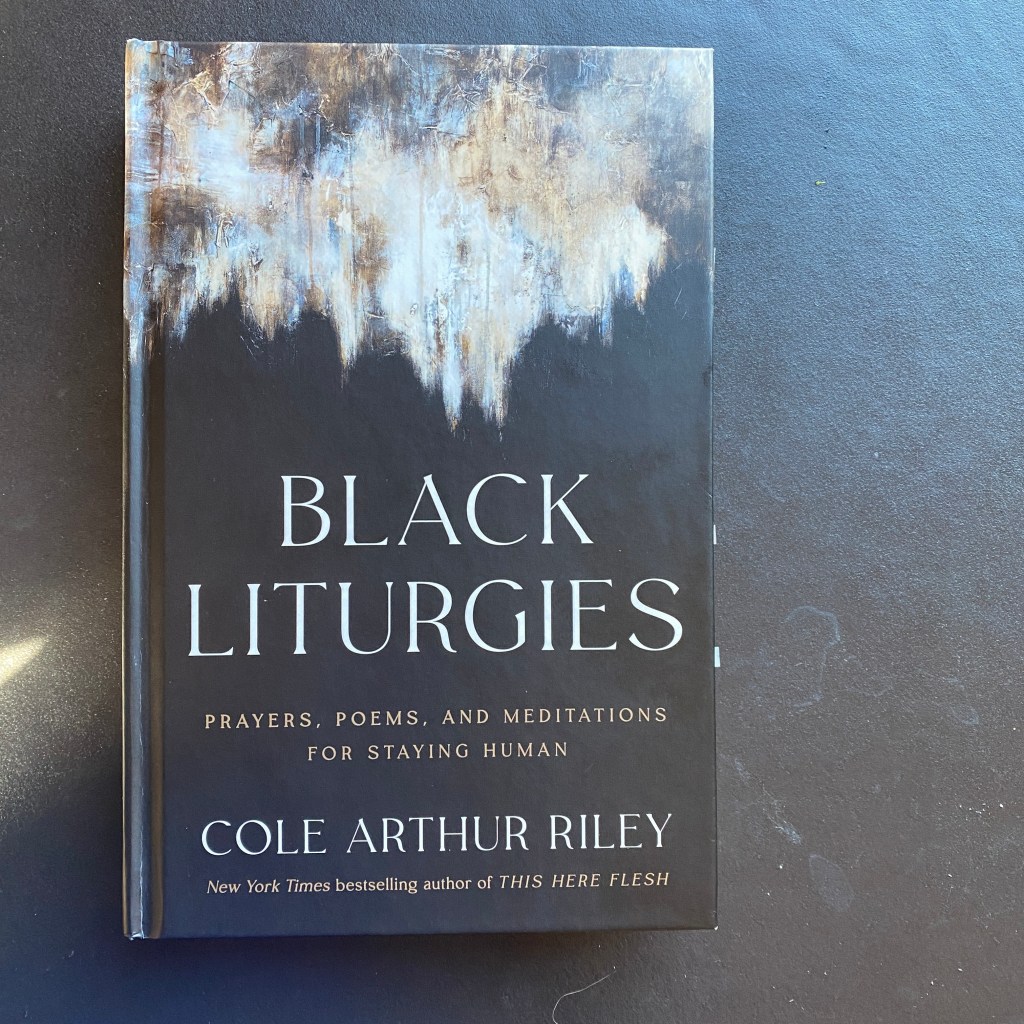

Black Liturgies by Cole Arthur Riley is one piece of content that found me because I was intentionally not watching British period pieces on Netflix (so to speak). In other words, I was making choices against the grain. I was being strange. Still am.

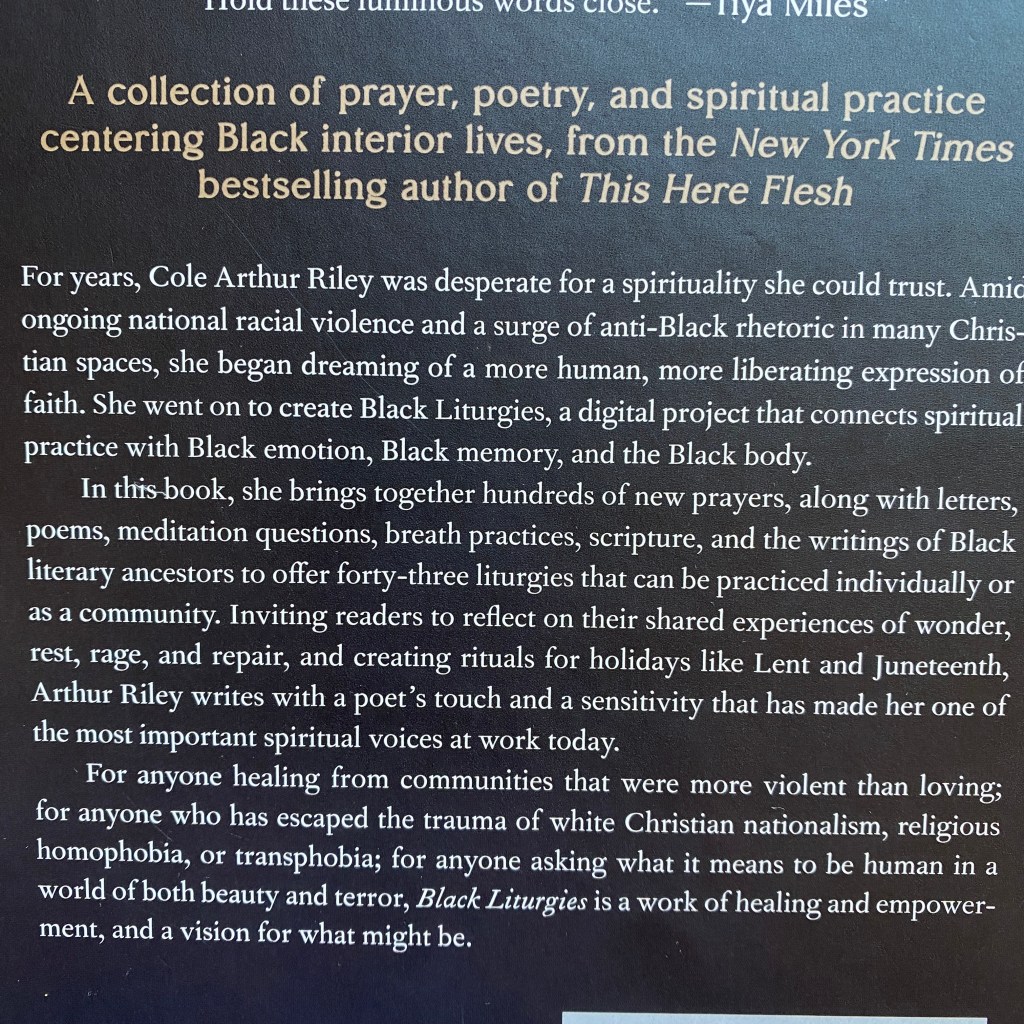

In this book, she brings together hundreds of new prayers, along with letters, poems, meditation questions, breath practices, scripture, and the writings of Black literary ancestors to offer forty-three liturgies that can be practiced individually or as a community. Inviting readers to reflect on their shared experiences of wonder, rest, rage, and repair and creating rituals for holidays like Lent and Juneteenth, Arthur Riley writes with a poet’s touch and a sensitivity that has made her one of the most important spiritual voices at work today.

For anyone healing from communities that were more violent than loving; for anyone who has escaped the trauma of white Christian nationalism, religious homophobia, or transphobia; for anyone asking what it means to be human in a world of both beauty and terror, Black Liturgies is a work of healing and empowerment, and a vision for what might be.

The vast majority of the texts that I read as part of my colonized education were white texts, but in yet another instance of colonizer deception, they weren’t labeled as such. Black Liturgies already steps out from this line of conformity by calling itself what it is. Strange indeed. I would have been saved a lot of time and heartache if all those white texts I encountered in school had been as upfront.

FOR THE UNKNOWN

God of shadows,

Our fear of the unknown keeps us from moving at all. Help us not to know. Protect our minds when anxious thoughts about the future refuse to leave us alone. Deepen our breath. Bring us into communities who can be trusted when they tell us we are safe. Comfort us when our minds become frenzied trying to determine what we cannot possibly know. When questions of what is to come or who will stay with us haunt us, make us kind with our own self talk, tender to our bodies, loving with all we do have control over. When no amount of courage can diminish fear’s power over us, remind us that we too have power as we rise to meet it. Provide a way to peace. We will not fear the dark. Ase.

(From Black Liturgies by Cole Arthur Riley.)

Again, I’m not Black but I’m reading a book called Black Liturgies. (Not just reading but returning to again and again for comfort and wisdom and strength and reminders of my own humanity.) Strange indeed. And yet this text spoke more to me than all the combined white texts that I was given in school. Stranger still. And I’m finding it to be pretty nice in this sea of strange.